Electricity Market Design: Views from European Economists

Europe has faced – and still faces – an unprecedented energy crisis that has translated into record-high gas and electricity prices, further propagating through the entire European economy. The rise in energy costs has been the main driver of inflation, whose EU average reached 11.5% in October 2022, pushing the ECB to increase interest rates. Inflation, coupled with the hike in interest rates, has reduced European households’ disposable income and purchasing power, put the competitiveness of European industry at risk, and forced governments to implement – subject to their asymmetric fiscal capabilities – costly support mechanisms to mitigate some of the economic and social consequences of the energy crisis.

These events have put electricity market design under the spotlight. The question is not only how to avoid the energy crisis from repeating itself in the future, but also how to promote low-carbon investments at the scale and speed necessary to decarbonize our economies while preserving security of supply. Following the words of the President of the European Commission in her State of the European Union Speech (“we will do a deep and comprehensive reform of the electricity market”), the shared view now is that these endeavors call for an electricity market reform. The question is: in which direction?

In this context, the European Commission has launched a public consultation on the electricity market reform. As European economists, we would like to share our views regarding key issues in the debate – space and time limitations prevent us from offering a broader discussion on all matters.

Short-run electricity markets should be preserved

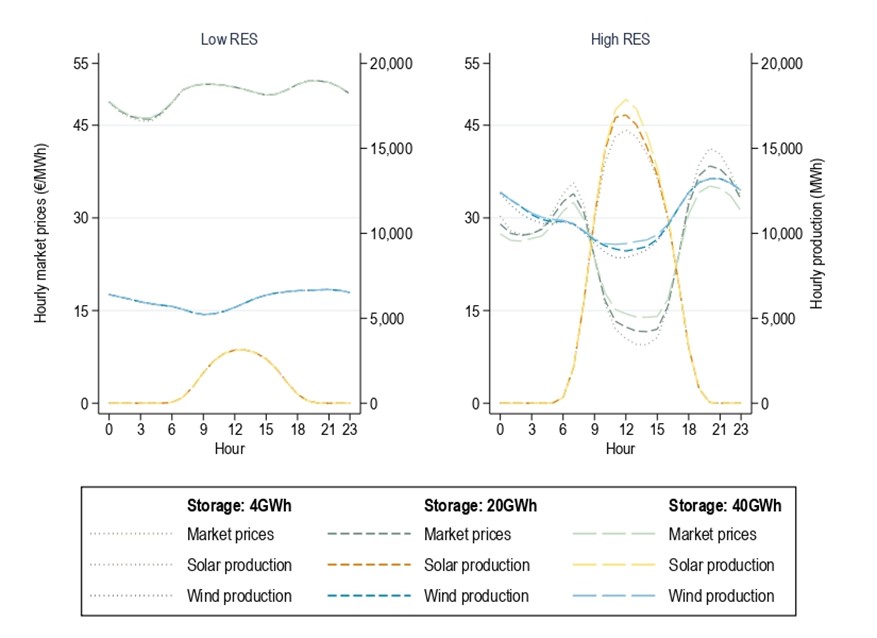

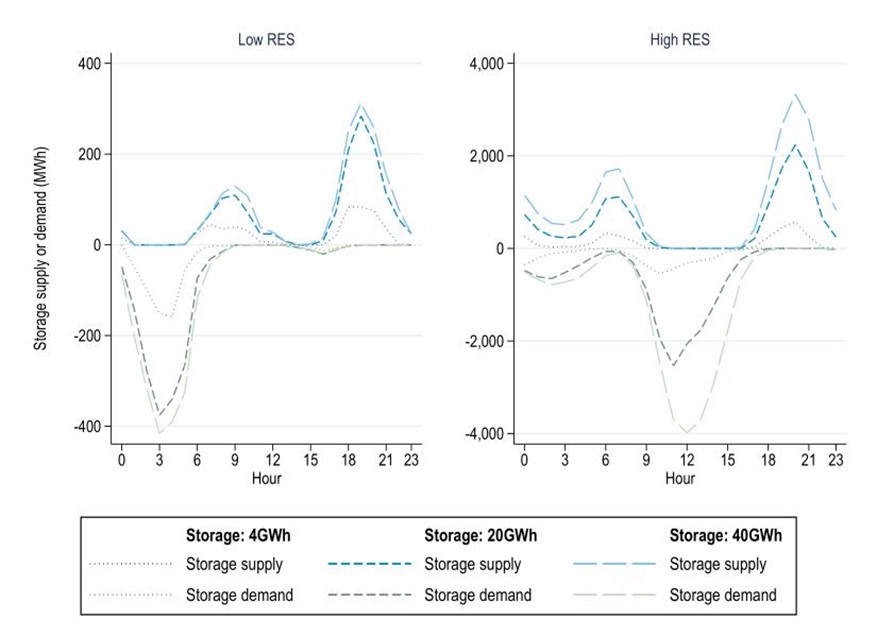

Overall, we support the consensus on preserving short-run electricity markets. These markets provide an indispensable tool to achieve efficiency in production and provide the right signals for efficient consumption. In particular, short-run prices are instrumental in guiding the efficient operation of some generation assets (including hydro, energy storage, and demand side flexibility, to name just three). However, we also share the view that reliance on short-run markets alone is inadequate as they are overly volatile, they do not reflect the average costs of the various generation technologies, and they fail to provide efficient market signals for long-run investments, both on the supply side (e.g., investments in renewable energies) as well as on the demand side (e.g., investments in electrification by industry). A priority of market design should be to facilitate healthy long-run contracting arrangements capable of addressing those concerns.

Long-term contracting should be promoted

At the core of the electricity market reform rests the need to ensure sufficient long-term contract coverage of producers and consumers at competitive prices. Long-term contracts protecting producers and consumers against cost and revenue shocks should be designed to also reduce electricity prices while strengthening the ability and incentives for participation in short-term markets. If designed cleverly, long-term contracting will enhance the functioning of short-term markets by (i) reducing risks related to regulatory interventions or technological breakthroughs, (ii) limiting incentives for exercising market power, and (iii) allowing for more entry and broader participation.

Despite the consensus on the need to strengthen long-term contracting, how to achieve this goal is intensely discussed. Two main options are: (i) bilateral private contracts, known in the electricity jargon as Power Purchasing Agreements (PPAs); and (ii) auctions for contracts for differences (CfDs) run and underwritten by regulators on behalf of consumers. Beyond the current discussions in electricity markets, economists have discussed the merits and demerits of these two market designs for a long time. And despite the potential trade-offs, one conclusion should be clear: it is incorrect to believe that (i) only PPAs are a market-based solution, capable of delivering the necessary scale of investment in the coming years, and that (ii) CfDs involve state support and should only be used when the market fails. These misconceptions, implicit in the European Commission’s public consultation document, risk biasing the assessment of how to organize long-term contracting in electricity markets.

In the context of electricity markets, we consider it important to keep in mind the following aspects in any comparison of PPAs versus CfDs:

PPAs alone are not fit to deliver low-carbon investments at the scale and speed needed

PPAs between generators and large energy-intensive firms have allowed for a first set of renewable investments to be pursued in several EU member states. This has notably been the case in Spain and the Scandinavian countries, where 13-20% of the total contracted capacity is contracted through PPAs. Efforts should be devoted to understanding why PPAs exist in some countries and not in others, and assessing the price impacts of PPAs on the end-users and not just their total volume. In any event, it is unlikely that PPAs will deliver the scale of renewable energy investments at the speed necessary to achieve the energy security and climate objectives agreed upon at the EU and Member State levels. Retail companies cannot underwrite sufficient volumes of PPAs because of the considerable uncertainty about future prices and quantities. Should it turn out that long-term PPA prices exceed shorter-term wholesale prices, retail competition would allow consumers to switch to other retailers that can afford to offer lower prices. Likewise, electricity-intensive industrial consumers cannot underwrite PPAs at a significant scale because their value in companies’ books will vary with changes in expectations of power prices to levels that, in some cases, would likely exceed the value of the companies themselves. Furthermore, should short-run electricity pricesfall below long-term contract prices, industrial players tied to PPAs would lose competitiveness viz à viz other industrial competitors who procure their power at spot market prices.

PPAs involve significant counterparty risks and are only suitable for large market players

For project developers, PPAs for long durations involve significant counterparty risks. First, private buyers – typically large energy-intensive companies and energy retailers – find it difficult, if not impossible, to guarantee that they will keep consuming the committed amounts of power in 10 to 20 years, for which a necessary condition is being active in the market by then. To avoid the temptation to renege from those PPAs should future electricity prices turn out lower than anticipated, PPAs need to be secured with corporate guarantees, which are costly and might create liquidity problems. The counterparty risks involved in PPAs increase financing costs and translate into substantial increases in the levelized costs of energy.

To date, PPAs have primarily been underwritten by publicly owned companies, financially strong energy-intensive companies for a small share of their total energy needs, or large companies for which energy costs are a minor cost component, such as major IT companies. There is no evidence that the industry can scale up the share of energy contracted under long-term PPAs to the level of renewable investment envisaged for the next decade. Furthermore, the complexity of PPA contracts and the uncertainty of coordinating consortia to underwrite PPAs at the demand side further limit the ability of smaller players to participate in these contracts. They thus create a bias benefiting larger players and therefore risk participation, competition, and further development of project pipelines by smaller actors.

Markets for PPAs are subject to competitive concerns, and the PPA prices are not necessarily passed on to the end-users

Markets for PPAs are opaque because the private contracts between the parties remain confidential. Opacity contributes to weakening competition, creates barriers to entry for new players, and weakens the signal for long-run investments. Furthermore, when energy retailers sign PPAs, there is no guarantee that they will share the potential savings achieved through PPAs with their customers. The reason is that energy retailers will price electricity at the resulting equilibrium price in the retail market, regardless of the price at which they buy electricity upstream. Lastly, PPAs risk draining liquidity from short-term energy markets, negatively affecting competition and productive efficiency, unless some provisions are put in place to guarantee that energy subject to PPAs is also offered in the wholesale market.

Benefits of PPAs and scope for improvement

Despite the above concerns, PPAs can play a role in various dimensions. First, in the absence of other long-term contracting options, PPAs have provided a contracting mechanism for firms that can credibly sign long-term contracts for a share of their energy needs. Second, they may provide additional contracting flexibility that can be tailored to the specific needs that counterparties might have, including the desire of industrial players to hedge their energy prices when planning their decarbonization electrification strategies. Third, PPAs will likely provide an instrument for investments in lifetime extension for existing renewable assets.

However, the problems outlined above suggest scope for improvement. For instance, to avoid opacity, firms should be required to make the contract terms publicly available through a central registry. Also, auctions of standardized PPAs should be favored over bilateral negotiations to enhance competition.

In any event, PPAs alone will be insufficient to unlock the needed investments and are inadequate for the vast part of energy consumers who cannot sign or benefit from those contracts. Furthermore, counterparty risks and the temptation to renege from PPAs seem unavoidable – and we do not recommend using public guarantees to overcome this, as this might require large amounts of public money while giving rise to moral hazard problems. Crowing out of PPAs by CfDs, if that were to happen, should not be a concern – the objective is not to have PPAs per se but rather that the overall volume of long-term contracting is achieved at competitive prices for end-users.

Regulatory-backed auctions for CfDs do not face these limitations

Publicly-backed auctions for CfDs do not face these limitations and thus offer a credible investment perspective for delivering the required volumes of renewable energy projects, which have already been set both nationally as well as at the European level. Regulatory-backed contracts are therefore also essential to unlock the investments into an EU supply chain of renewable energies’ manufacturing capacity. A CfD model has already been successfully implemented in various EU countries, achieving significant participation in the auctions and large price reductions. In particular:

- Governments can auction the volume of CfDs required to meet energy needs domestically and through joint renewable tenders of several countries. This creates a credible investment framework for investments in renewable projects as well as in the whole value chain. Levelised costs of renewable energy could decline significantly compared to PPA structures thanks to reduced counterparty risk.

- Auctions are effective mechanisms for extracting investors’ information about their actual costs if appropriately designed. Competition through auctions will thus allow consumers to benefit from the lower costs of renewable investments. Efforts should be put into the design of these auctions to promote ample participation and competitive outcomes.

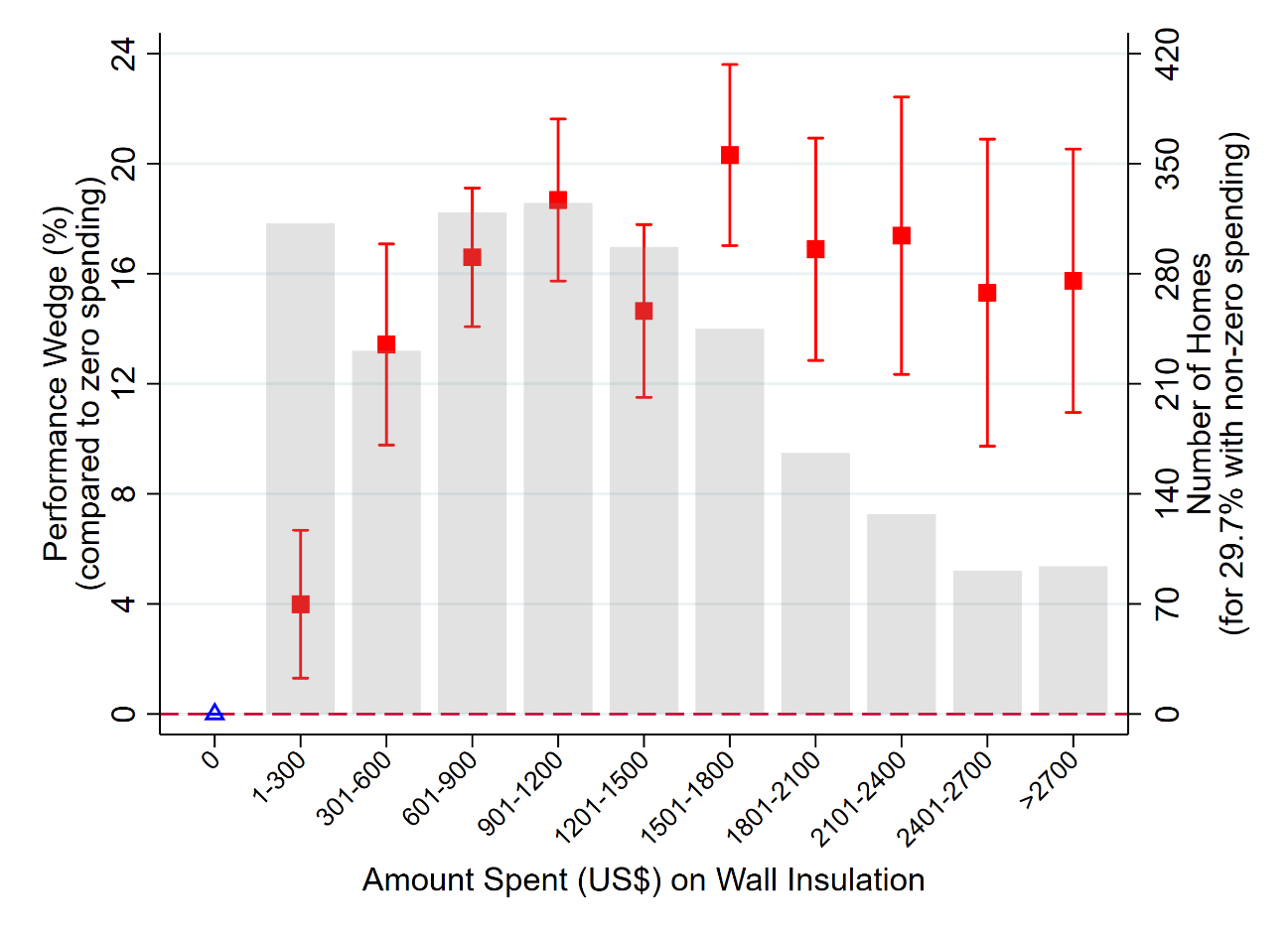

- In particular, the CfD auctions can be designed to reward system-friendly production profiles to ensure the alignment of today’s investment choices with the needs of the transforming energy system. They can also be designed to avoid large inframarginal rents, thus contributing to an affordable and competitive energy supply. Related to this, the interplay with PPAs needs to be well designed so as to avoid the projects at the best resource locations cherry-picking PPA structures, which would result in higher costs for consumers.

Government (agencies) can pool these underwritten CfDs and pass them to final consumers (or retail companies on their behalf) in ways that do not distort the short-run price signals or 5 retail competition. Thus, consumers can be hedged against wholesale price volatility while they remain incentivized to hedge (and realize their own flexibility potentials). We recommend allocating access to the CfD prices independently of current consumption to ensure marginal incentives for energy efficiency and investments in flexibility are maintained. For instance, for households, the allocation could be conditional on demographics (family size, income, climate zone) to address distributional concerns and enhance acceptance by the local communities. Each Member State could implement its own procedures depending on its country’s realities. However, all Member States should ensure that the mechanism is transparent, easy to comprehend, and passed through to final consumers.

As an additional benefit of regulatory-backed CfDs, a simplified and stable contracting environment can ease the burden on project developers. Along these lines, the permitting process for renewable installations can be difficult and time-consuming, and more public resources should be devoted to facilitating it.

Limits on inframarginal generators should be maintained

Beyond the debate on long-term contracting, a contentious issue is whether to limit the revenues of the existing inframarginal generators (nuclear, hydro, and renewables). As the President of the European Commission acknowledged, these plants “are making in these times – because they have low costs, but they have high prices on the market – enormous revenues…revenues they never dreamt of; and revenues they cannot reinvest to that extent. These revenues do not reflect their production costs.”

We believe some form of revenue limitations on the inframarginal generators should be maintained. These measures, which were put in place under extreme conditions, should be embraced as a coordination success in moments of critical tension. Given that the market will probably experience extreme conditions in the future, and the challenges experienced will repeat, it is best to retain a safety valve. Having a pre-defined mechanism in place will avoid all the challenges emerging from the interaction with pre-existing contracts and the turmoil observed during the energy crisis, during which governments had to make quick decisions to limit the burden of energy costs to businesses and households while assuming substantial debt.

There are some economic principles that these revenue limitations should respect. First, revenue limitations should be implemented without distorting the marginal signal for the relevant price ranges in the wholesale market. This can be achieved by a number of approaches, including a constant rate per unit of output reduction in revenues or the dispatch of strategic reserves once price levels reach a pre-agreed price level. This can be considered to replicate approaches common in international markets that trigger those mechanisms only with sustained high prices, exempting short-lived price spikes. Second, the limit must be high enough to be considered “unexpected” under business-as-usual conditions. This will ensure that there are no investment distortions. As a notable exception, legacy technologies, such as large hydro projects and nuclear plants built prior to liberalization, have been developed as public projects and are not subject to concerns about investment incentives. Member States could implement stricter revenue limits for these legacy plants without impacting the efficiency of the market.

Finally, keeping inframarginal revenue limits can also mitigate the contracting risk associated with sustained high marginal prices like the ones we have observed during the energy crisis. These policies reduce the extent to which firms may fail to comply with or even profit from breaching their contracts and foster a healthier contracting market. They also contribute to making the auctions for CfDs more competitive to the extent that the outside option of selling directly in the short-run market becomes less attractive. Last, it is important to note that these measures would only be triggered under episodes of sustained high prices or would apply to legacy plants. Hence, they would not alter the legitimate expectations of the plant owners and should thus not be considered expropriatory.

Conclusion

In sum, we welcome the European Commission’s initiative to open the debate on the electricity market reform. Europe’s industry and households cannot afford to pay high and volatile electricity prices much longer. The new electricity market arrangements should seek the two-fold objective of (i) providing market resilience in the event of future crises to electricity generation systems (e.g., due to increases in fossil fuel prices, droughts, or nuclear outages, among others) and (ii) promoting decarbonization at least cost and risks for firms and consumers.

To ensure a healthy long-term contracting environment, we call for caution regarding reliance on PPAs alone. On their own, PPAs are not fit to deliver low-carbon investments at the necessary speed and scale and are unlikely to benefit all consumers, particularly households and small and medium-sized companies. On the contrary, we see potential in regulatory-backed auctions of contracts for differences, which under adequate provisions, can co-exist with PPAs. This approach would help secure the needed investments, foster stronger competition among entrants, and drive down the costs of the investments through reduced counterparty risk, ultimately benefiting all consumers through lower electricity prices. As a remaining challenge for market design, it still needs to be defined how the two instruments should interplay.

Long-term contracts should be designed to strengthen the good functioning of short-run energy markets, which play a key role in promoting productive efficiency and flexibility. As a safety valve against future turmoil, we recommend keeping and improving the mechanisms to avoid inframarginal rents from escalating at huge societal costs.

A reform in this direction would be the best antidote against the fears of European deindustrialization and a big push to the European ambition of having a say in the Green battle.

Signatories:

Stefan Ambec (Toulouse School of Economics, France)

Albert Banal (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain)

Estelle Cantillon (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium)

Claude Crampes (Toulouse School of Economics, France)

Anna Creti (University Paris Dauphine, France)

Francesco Decarolis (Bocconi University, Italy)

Natalia Fabra (Carlos III University and EnergyEcoLab, Spain)

Reyer Gerlagh (Tilburg University, Netherlands)

Karsten Kneuhoff (DIW, Germany)

Camille Landais (London School of Economics, UK)

Matti Liski (Aalto University, Finland)

Gerard Llobet (CEMFI, Spain)

David Newbery (Cambridge University, UK)

Michele Polo (Bocconi University, Italy)

Mar Reguant (Barcelona School of Economics and Northwestern University, Spain)

Sebastian Schwenen (Technical University of Munich, Germany)

Iivo Vehviläinen (Aalto University, Finland)